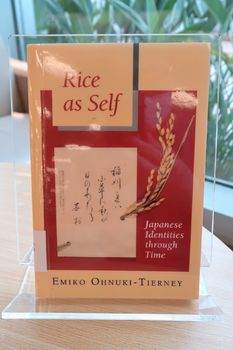

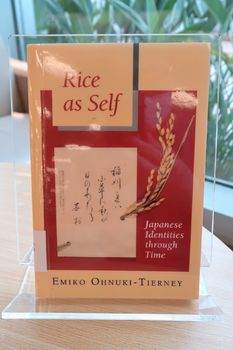

Rice as self : Japanese identities through time

Rice as self : Japanese identities through time 1. Food as a Metaphor of Self: An Exercise in Historical Anthropology -- 2. Rice and Rice Agriculture Today -- 3. Rice as a Staple Food? -- 4. Rice in Cosmogony and Cosmology -- 5. Rice as Wealth, Power, and Aesthetics -- 6. Rice as Self, Rice Paddies as Our Land -- 7. Rice in the Discourse of Selves and Others -- 8. Foods as Selves and Others in Cross-cultural Perspective -- 9. Symbolic Practice through Time: Self, Ethnicity, and Nationalism.

In this engaging account of the crucial significance of rice for the Japanese, Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney examines how people use the metaphor of a principal food, such as rice, corn, or wheat, in conceptualizing themselves in relation to other peoples who eat other foods. Rice as Self shows how the Japanese identity was born through discourse with the Chinese, the first historical other. It shows how rice agriculture, in itself introduced from outside, was, ironically, appropriated as a dominant metaphor of the Japanese self. Since then rice and rice paddies have served as the vehicles for their deliberation of selves and others. Using for evidence such diverse sources as myth-histories of the eighth century, the imperial accession ritual, woodblock prints, novels, day-to-day discourse, and opinion polls, Ohnuki-Tierney shows that throughout Japan's history the cultural importance of rice has been deeply embedded in Japanese cosmology, both of the elite and common folk - rice as soul, rice as deity, and ultimately rice as self of the family, the community, and the nation at large. This, she emphasizes, has been so even though rice has not been the ""staple food"" of the Japanese, as is commonly held. Using Japan as an example, Ohnuki-Tierney proposes a new and complex cross-cultural model for the interpretation of selves and others. The historical transformations of the Japanese identity have been intimately related not only to their encounter with foreigners - the external other - but also to the process of the marginalization of minorities within Japanese society - the internal other - and of external others who ceased to be the privileged other. The model takes into account the power inequities both within and outside a given society. It has broad applications, especially to people for whom foreign ""cultural hegemony"" is part and parcel of a complex, often ambivalent, process of self-identity.

Poster

Poster  Photo 8

Photo 8  Photo 7

Photo 7  Photo 6

Photo 6  Photo 5

Photo 5  Photo 4

Photo 4  Photo 3

Photo 3  Photo2

Photo2  Photo 1

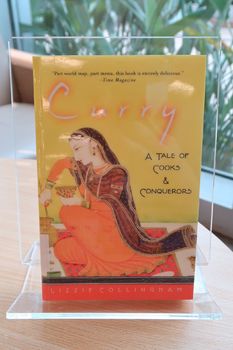

Photo 1  Curry : a tale of cooks and conquerors Chicken tikka masala : the quest for an authentic Indian meal -- Biryani : the great Mughals -- Vindaloo : the Portuguese and the chilli pepper -- Korma : East India Company merchants, temples and the nawabs of Lucknow -- Madras curry : the British invention of curry -- Curry powder : bringing India to Britain -- Cold meat cutlets : British food in India -- Chai : the great tea campaign -- Curry and chips : Syhleti sailors and Indian takeaways -- Curry travels the world. Traces the history of Indian cuisine from the imperial kitchen of the Mughal invader Babur to the cookhouse of the British Raj, profiling traditional dishes based on a long history of invasion and the fusion of different food traditions.

Curry : a tale of cooks and conquerors Chicken tikka masala : the quest for an authentic Indian meal -- Biryani : the great Mughals -- Vindaloo : the Portuguese and the chilli pepper -- Korma : East India Company merchants, temples and the nawabs of Lucknow -- Madras curry : the British invention of curry -- Curry powder : bringing India to Britain -- Cold meat cutlets : British food in India -- Chai : the great tea campaign -- Curry and chips : Syhleti sailors and Indian takeaways -- Curry travels the world. Traces the history of Indian cuisine from the imperial kitchen of the Mughal invader Babur to the cookhouse of the British Raj, profiling traditional dishes based on a long history of invasion and the fusion of different food traditions. Rice as self : Japanese identities through time 1. Food as a Metaphor of Self: An Exercise in Historical Anthropology -- 2. Rice and Rice Agriculture Today -- 3. Rice as a Staple Food? -- 4. Rice in Cosmogony and Cosmology -- 5. Rice as Wealth, Power, and Aesthetics -- 6. Rice as Self, Rice Paddies as Our Land -- 7. Rice in the Discourse of Selves and Others -- 8. Foods as Selves and Others in Cross-cultural Perspective -- 9. Symbolic Practice through Time: Self, Ethnicity, and Nationalism. In this engaging account of the crucial significance of rice for the Japanese, Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney examines how people use the metaphor of a principal food, such as rice, corn, or wheat, in conceptualizing themselves in relation to other peoples who eat other foods. Rice as Self shows how the Japanese identity was born through discourse with the Chinese, the first historical other. It shows how rice agriculture, in itself introduced from outside, was, ironically, appropriated as a dominant metaphor of the Japanese self. Since then rice and rice paddies have served as the vehicles for their deliberation of selves and others. Using for evidence such diverse sources as myth-histories of the eighth century, the imperial accession ritual, woodblock prints, novels, day-to-day discourse, and opinion polls, Ohnuki-Tierney shows that throughout Japan's history the cultural importance of rice has been deeply embedded in Japanese cosmology, both of the elite and common folk - rice as soul, rice as deity, and ultimately rice as self of the family, the community, and the nation at large. This, she emphasizes, has been so even though rice has not been the ""staple food"" of the Japanese, as is commonly held. Using Japan as an example, Ohnuki-Tierney proposes a new and complex cross-cultural model for the interpretation of selves and others. The historical transformations of the Japanese identity have been intimately related not only to their encounter with foreigners - the external other - but also to the process of the marginalization of minorities within Japanese society - the internal other - and of external others who ceased to be the privileged other. The model takes into account the power inequities both within and outside a given society. It has broad applications, especially to people for whom foreign ""cultural hegemony"" is part and parcel of a complex, often ambivalent, process of self-identity.

Rice as self : Japanese identities through time 1. Food as a Metaphor of Self: An Exercise in Historical Anthropology -- 2. Rice and Rice Agriculture Today -- 3. Rice as a Staple Food? -- 4. Rice in Cosmogony and Cosmology -- 5. Rice as Wealth, Power, and Aesthetics -- 6. Rice as Self, Rice Paddies as Our Land -- 7. Rice in the Discourse of Selves and Others -- 8. Foods as Selves and Others in Cross-cultural Perspective -- 9. Symbolic Practice through Time: Self, Ethnicity, and Nationalism. In this engaging account of the crucial significance of rice for the Japanese, Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney examines how people use the metaphor of a principal food, such as rice, corn, or wheat, in conceptualizing themselves in relation to other peoples who eat other foods. Rice as Self shows how the Japanese identity was born through discourse with the Chinese, the first historical other. It shows how rice agriculture, in itself introduced from outside, was, ironically, appropriated as a dominant metaphor of the Japanese self. Since then rice and rice paddies have served as the vehicles for their deliberation of selves and others. Using for evidence such diverse sources as myth-histories of the eighth century, the imperial accession ritual, woodblock prints, novels, day-to-day discourse, and opinion polls, Ohnuki-Tierney shows that throughout Japan's history the cultural importance of rice has been deeply embedded in Japanese cosmology, both of the elite and common folk - rice as soul, rice as deity, and ultimately rice as self of the family, the community, and the nation at large. This, she emphasizes, has been so even though rice has not been the ""staple food"" of the Japanese, as is commonly held. Using Japan as an example, Ohnuki-Tierney proposes a new and complex cross-cultural model for the interpretation of selves and others. The historical transformations of the Japanese identity have been intimately related not only to their encounter with foreigners - the external other - but also to the process of the marginalization of minorities within Japanese society - the internal other - and of external others who ceased to be the privileged other. The model takes into account the power inequities both within and outside a given society. It has broad applications, especially to people for whom foreign ""cultural hegemony"" is part and parcel of a complex, often ambivalent, process of self-identity. 地方創生 : 小型城鎮、商店街、返鄉青年的創業10鐵則

地方創生 : 小型城鎮、商店街、返鄉青年的創業10鐵則  Ghetto at the center of the world : Chungking Mansions, Hong Kong

Ghetto at the center of the world : Chungking Mansions, Hong Kong  Sustainability in contemporary rural Japan : challenges and opportunities

Sustainability in contemporary rural Japan : challenges and opportunities  廚房裡的人類學家 = Anthropologist in the kitchen

廚房裡的人類學家 = Anthropologist in the kitchen  香港的顏色 : 南亞裔 : 歷史, 文化, 傳略, 美食, 購物

香港的顏色 : 南亞裔 : 歷史, 文化, 傳略, 美食, 購物  認識香港南亞少數族裔

認識香港南亞少數族裔  At the South-East Asian table

At the South-East Asian table  Information

Information  Usa Jingu

Usa Jingu  Matama Beach

Matama Beach  Background of Futagoji Temple

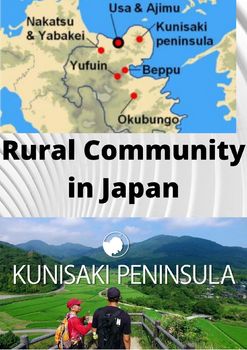

Background of Futagoji Temple  Rural Community in Japan

Rural Community in Japan  下一站:土瓜灣

下一站:土瓜灣  品嚐東南亞!

品嚐東南亞!